The Hammer and The Dance

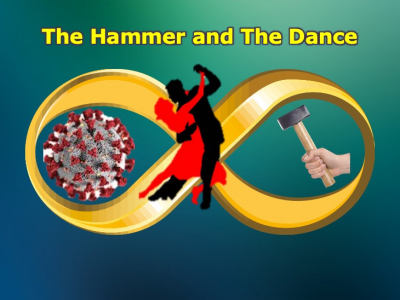

Metaphors matter, especially in uncertain times, when the only way to frame a complex predicament is to use models from a familiar past. The title of this blog borrows from Tomas Pueyo’s excellent article and the picture that accompanies it is a mashup of one of my ecological images and it.

Metaphors matter, especially in uncertain times, when the only way to frame a complex predicament is to use models from a familiar past. The title of this blog borrows from Tomas Pueyo’s excellent article and the picture that accompanies it is a mashup of one of my ecological images and it.

When it comes to the coronavirus, war metaphors abound. British politicians summon the spirit of the Blitz, while Donald Trump describes himself as “a war-time President.” These bellicose approaches have rhetorical value and may help address logistical issues, but we need additional views. Ecological analogies supply a helpful lens. For, from an ecological/business perspective, the coronavirus is the ultimate entrepreneur. If the purpose of an entrepreneur is to create a customer, the coronavirus is superb! In a population without immunity every human is a potential “customer.” This vulnerability is increased by globalization and global travel and aggravated by long just-in-time supply chains, tuned to efficiency rather than resilience.

What’s more, everyone infected with the coronavirus “recommends” it persuasively to others, with an average of 2.4 other people becoming infected. In marketing the well- known net promoter score is measured by asking customers the question, “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely is it that you would recommend our organization (product) to a friend or colleague?” Those who score 0-6 are classified as “detractors,” those who measure 7-8 are ‘passives’ and those with a score of 9-10 are “promoters.” You add up number of responses that fall into each of the three categories and calculate the percentage that each category represents of the total. Then subtract the percentage of detractors from the promoters and the result, expressed an as integer, is your net promoter score. It ranges from +100 to -100. With all customers very likely to recommend it to others, the coronavirus’ net promoter score would be a perfect +100!

The Case for Crushing the Coronavirus with Coercive Bureaucracy

So the coronavirus represents the inverse of the question that currently preoccupies managers around the world – how to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation in large, mature organizations. Now we want to crush this dangerous disruptive innovation. How do we do that? The long-term solution is clearly an effective vaccine that, like the polio shots, will stop the disease in its tracks and eliminate its ability to create customers. But that is going to take 12-18 months and there is no guarantee that the search will be successful. Even if it is, the coronavirus will probably mutate and, like the flu, may become a moving target, rendering vaccines only partially protective. If that’s the case the long- term default will be to so-called herd immunity, where 60-70% of a population becomes immune and hinders the spread of infection. In that process epidemiologists suggest that 10-20% of the world’s human population may die: far too high a toll, but still less than the Black Death, the deadliest pandemic ever, that is estimated to have killed 30-60% of the population.

In the short-term we are going to have to turn to that proven killer of innovation of all kinds – coercive bureaucracy – Pueyo’s “hammer.” In effect this is what social distancing does. Enforced by a dominance hierarchy, it restricts communication to the bare essentials for short-term performance (survival). All extraneous contacts and conversations are strongly discouraged, and the bandwidth of any communications is kept as thin as possible. The intention is to isolate individuals and prevent the formation of any informal communities or communication at close quarters that might spread the virus to more customers.

We know that coercive bureaucracies reliably destroy innovation in corporate environments, but the key question is whether they can work in cities rather than in organizations against such a small, fast disruptor. Geoffrey West of the Santa Fe Institute has done extensive work contrasting corporations with cities. Both show economies of scale as they grow – a city doubling in size doesn’t need twice as many gas stations, only about 1.85 times as many. But as cities grow their outputs grow faster than they do. As a result, there is more creativity and innovation and higher wages but also more crime and more communicable diseases. According to West, in contrast with cities all corporations eventually die. This begs the question, Why?

West based his perception in part on flawed measurement of corporate vitality. He observed that corporations die when they stop reporting financial results. So he records YouTube as having died when it was acquired by Google in 2006. Yet it is stronger and healthier organization than before. These data flaws aside, however, West’s hunch is that cities tolerate fringe activities much more readily than corporations do. The corporate focus on performance, the technologies that support their processes, and their emphasis on short-term results combine together with the imperatives of economies of scale to overwhelm the innovation dynamics present at their founding. Cities, which are not shackled to a single value chain, have more diffuse authority structures and face no such constraints. So, can social distancing suppress our social selves long enough to be effective? Can we really shut down society enough? Probably not, which means that after the “hammer” of suppression comes the “dance” of accommodation, as we learn to live with virus and the disease.

We are living inside the experiments being conducted in cities and communities around the world. Will the draconian approach of China be successful, or will they experience subsequent waves? What about the informal controls used in Sweden? How about the Dutch strategy to achieve ‘herd immunity’? Why is Spain’s mortality rate so high and Germany’s so low? And so on. Time will tell but, in the meantime, stay healthy!

This post was contributed by David K. Hurst

A Catalyzing Story Conversation with David Hurst

Plexus Institute published David Hurst’s piece, Discovering Complexity: A Story of an Organization in Crisis and its Response, through The Catalyzing Stories Project. Listen to the podcast conversation with David Hurst FRSA and Prucia Buscell’s about how his organization was thrown into crisis by an ill-advised takeover on the eve of a sharp recession. David’s ecological model maps the trajectories of complex systems in space and over time and offers valuable insight into the surprising conditions of current day events.

The New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI) has taken a leadership role in organizing an action network endCoronavirus.org to minimize the impact of COVID-19 by providing continually updated and useful data and guidelines for action. We will share updated information and work emerging within our network through the newsletter, in posts and social media to help our network members stay informed of rapidly changing information.