When Lucille Conlin Horn was born in 1920, a fragile infant weighing only two pounds, she was not expected to live. Her twin sister died. But Lucille Horn did live for nearly a century, with a career, marriage and five children.

Her survival is part of an extraordinary story of the wonderful, surprising and sometimes wrenching ways that innovations are introduced, resisted, and travel in unexpectedly circuitous routes before eventual adoption.

In the late 1870s, a French obstetrician named Stephane Tarnier visited a Paris zoo and noticed chicken hatchlings wobbling about in a box warmed by containers of hot water. He thought about the horrifying infant mortality rate at his hospital, and wondered if a warm temperature controlled enclosure might save premature human babies. Tarnier had similar box built for his tiny patients. Steven Johnson, writes about Tarnier’s achievement in his book Where Good Ideas Come From. While 66 percent of low weight babies were dying in the weeks after birth, 72 percent of low weight babies in the mew warming box survived. Johnson writes that good ideas are “works of bricolage,” in which existing notions and practices are cobbled together for new purposes. He calls it the adjacent possible, an idea he adapted from theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman. After a few years, all Parisian hospitals had infant incubators.

But most of the medical establishment in Europe and the U.S. resisted the idea and incubators were not allowed in most hospitals. Incubators were not common is U.S. hospitals until after World War II.

In 1888 another French physician, Pierre-Constant Budin, now considered the father of modern neonatology, began publishing results of Tarnier ‘s work. The medical community remained dubious. Budin and colleagues, trying to spread the life-saving methods, arranged exhibits of infant incubators in Berlin and London, and at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900, and the World’s Fair in Buffalo New York in 1901.

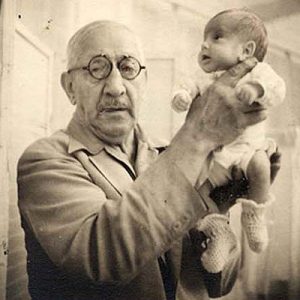

Dr. Martin Couney holds Beth Allen, one of his incubator babies, at Luna Park in Coney Island. This photo was taken in 1941. Courtesy of Beth Allen

Martin Arthur Couney, who was born March 1, 1870 came to the U.S. in the 1890s, claimed to be a physician and a student of Budin. Neither may have been true, though he apparently did help with some of the successful early exhibits of live babies in incubators. Whatever his credentials, he is credited with saving the lives of thousands of premature babies through a side-show exhibition at Cony Island, N.Y. that opened in 1903 and continued for four decades. Couney charged people 25 cents for admission to see the babies in his exhibit, and used the money to cover the cost of the equipment and a team of skilled nurse to care for the babies. Hundreds of thousands of curious visitors came. Carnival barkers,including a young Cary Grant, urged the crowds to come look. Parents did not have to pay.

Coney Island was famous for its side shows-it featured bizarre displays such as the limbless lady, the man three legs, the man with the face of a lion and other oddities. Showing live premature babies was controversial, and so was Couney. Many considered him more charlatan or showman than life-saver, though he did have highly credentialed friends, and was gratified to know hospitals began using incubators shortly before he died in 1950. His own daughter was premature, and survived in one of his incubators. He also had appreciation of thousands of survivors, many of whom attended his graduate reunions. The amusement park atmosphere may have both hindered and helped mainstream medical acceptance. In the Horn obituary, the AP reported Couney had said more than 8,000 infants were placed in his incubators, and more than 7,000 survived.

Lucille Horn, who died February 10, 2017 at he age of 96, was buried next to her premature twin who could not be saved. She told her story to NPR and others. In the early 20th century, hospitals couldn’t do much for tiny premature babies so they were sent home with little chance of living. Lucile Horn says her father, having been told his surviving twin baby faced death, begged Couney to accept her in his exhibit. After a six-month stay, she says, she was returned to her family and went on to live a long full life. She worked as a crossing guard and a legal secretary for her husband in addition to having five children.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.