For Love of Science, Music,and Medicine

When a young music teacher stayed awake and played the saxophone during surgery to remove his brain tumor, it was part of an extraordinary six-month collaboration. The teacher wanted to be reassured he wouldn’t lose his musical ability. The medical team wanted to know more about how the brain processes music.

Dan Fabbio was teaching music and finishing his Master’s degree in music education in the spring of 2015 when dizziness, nausea and oddly hallucinatory sights and sounds sent him to the hospital. He was 25 and had been in good heath. After having a CAT scan, doctors told him he had a mass in his brain. He was referred to the University of Rochester’s Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience. There he met neurosurgeon Web Pilcher, MD, PhD, a professor and chair of the Department of Neurosurgery, who had earlier teamed with Brad Mahon, PhD, an associate professor in UR’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences to develop a sophisticated Translational Brain Mapping Programfor patients needing surgery to remove tumors or control seizures.

Mapping the Brain for Music

The brain maps are developed for each patient, based on a battery of tests that identify such important functions as motor control and language processing that maybe located near a tumor and potentially disrupted by the surgery. Human brains are organized in more or less the same way, Mahon explained in a UR press release. “But the particular location at a fine grain level of a given function can vary up to a couple centimeters from one person to another. So it’s very important to carry out this kind of detailed investigation for each patient.” Tumors and surgery can damage brain tissue and disrupt communication between different parts of the brain, Pilcher explained, so precise information about each individual’s brain is vital.

Fabbio made it clear to his doctor that music was his life, his passion ad his profession. As Pilcher explained in an NPR interview, his team had mapped the brains of hundreds of people, including doctors, lawyers, a bus driver and a furniture maker. But they had never mapped a musician. So they turned to Elizabeth Marvin, PhD, a professor of music theory at UR’s Eastman School of Music. Marvin, who also holds a position in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Science, studies music cognition, the ability of the brain to profess and remember music.

Marvin and Mahon developed tests for Fabbio to perform while having fMRI scans of his brain. He’d listen to short melodies and hum back the tune. Then he’d do language tasks, such as identifying objects and repeating sentences. The fMRI detects changes in oxygen levels, so the parts of the brain activated during the tests helped identify brain areas important for music and areas important for language. Fabbio’s brain map showed the location of the tumor-which was not malignant-and it was near the area of the music function.

The doctors wanted to know whether they were successfully saving Fabbio’s musical ability, so they asked him to bring his saxophone into the operating room and, if possible, play it during surgery. Fabbio knew that his brain would be exposed during surgery, and doctors warned that the breath needed for long notes could make his brain protrude beyond the skull. So Fabbio and Marvin settled on a gentle version of a Korean folk song that could be played with short, shallow breaths while he was lying down. He was awake and performing musical tasks during the surgery. When the tumor was out, Fabbio played the Korean tune flawlessly. An emotional operating room staff burst into applause.

A few months after the surgery, Fabbio was playing, enjoying and teaching music again. Marvin, who had monitored his musical responses throughout the operation, reflected on her experience. “The whole episode struck me as quite staggering that a music theorist could stand in an operating room and somehow be a consultant to brain surgeons,” she said. “It turned out to be one of the most amazing days of my life because it felt like all my training was suddenly changing someone’s life, and allowing thus young man to retain his musical abilities.”

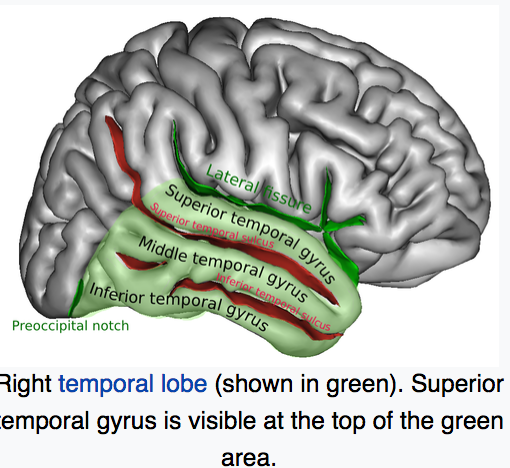

The research is described in an article in Current Biology. The mapping and research suggest that the right posterior superior temporal gyrus (STG) in the human brain is specialized for aspects of music processing.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.